Touring Agricultural Investment Projects

A two-week trip explores how to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of agricultural investment tools in Africa.

A two-week trip explores how to maximize the benefits and minimize the risks of agricultural investment tools in Africa.

Day Eleven: Final thoughts on the potential of agropoles and agricultural corridors

Day Ten: Sunflower and green beans: women, bet on the future!

Day Nine: The power of an entrepreneur

Day Eight: Harnessing irrigation's potential in Tanzania

Day Seven: Farewell to Burkina

Day Six: Learning from experience

Day Five: Jobs, jobs, jobs

Day Four: At Bagrépôle, steps forward but still more to do

Day Three: The view from Madagascar

Day Two: At issue, land rights

Day One: Our journey begins...

Day Eleven: Final thoughts on the potential of agropoles and agricultural corridors

Our journey is coming to an end and we wanted to gather the impressions and lessons of our fellow traveller, Nicolas Kobiane, the Secretary General of Bagrépôle. He says that the two stages of the mission in Burkina Faso and Tanzania were necessary to better understand the complexity of the approaches entailed in agropoles and agricultural corridors.

"It is essential that this type of initiative be based on political commitment. This must be permanent and support the entire process," he says. "Both initiatives are ongoing experiences that must be analyzed over the long term. And although different, there are several similarities between SAGCOT and Bagrépôle with regard to their objectives and challenges. We must take this into account and manage them properly in order to ensure a successful investment."

Both approaches aim at agricultural growth, poverty reduction, and the opening up of landlocked areas based on agricultural policies that rely on investments in agribusiness and infrastructure development, he points out. According to Kobiane, agropoles, like agricultural corridors, are designed to be a viable and sustainable response to structural problems and to make agriculture a driving force for stimulating the rural economy.

He acknowledges the major challenges associated with this type of project, including population displacement, social conflicts and environmental protection. He suggests successful land management needs to allocate land in such a way as to integrate both small and large producers into agropole projects, as well as to promote agricultural aggregation.

"Land is an essential capital of the agropole," he points out. "The importance of compensation mechanisms for people affected by the project and the commitment of beneficiaries to the project should not be overlooked. In Bagrépôle, in addition to compensation for crop loss and land-for-land compensation, we have planned accompanying measures to facilitate the economic development of the land allocated to the people affected by the project in the irrigated area.”

These two experiences, Bagrépôle and SAGCOT, are based on spatial planning projects, notes Kobiane. "The identification of the area and compliance with the national master planning scheme are priority elements to enhance the potential of these approaches.” In addition, he says, "the challenge is to have an entity that plays both the role of facilitator and coordinator between actors and facilitates links between companies. The mandate of these entities and their institutional anchoring must be consistent with the objectives pursued.”

He adds: "Structuring public investments is the backbone for the success of agropoles, but the problem is financing: these initiatives are expensive and require significant resources. Financing strategies such as public–private partnerships are needed." The development of infrastructure, which is to say energy, roads, hydro-agricultural developments, dams and even the security issue, contributes to the establishment of a favourable business climate in order to better mobilize the private sector.

Private investors are expected to transform these opportunities into dynamic, profitable companies that create wealth and sustainable jobs. Countries have implemented reforms with special incentives, including a favourable tax and customs regime or a single window to facilitate the completion of all procedures for carrying out economic activities. These are all instruments to attract a private sector that is, Kobiane notes, still very cautious.

Day Ten: Sunflowers and green beans: Women bet on the future!

Anjelina Kitime is a widow. She lives in Mgama, in the Iringa region of Tanzania. When her husband died, Anjelina found herself raising their children alone. To support them, she depends on the two-hectare plot she inherited from her husband.

Until recently, she dedicated her entire plot to the production of tomatoes, corn and potatoes. She used some of the vegetables to feed her family and as donations toward her children's school fees. The rest was sold at market.

Ten months ago, she was accepted into a project supported by the Clinton Development Initiative, a program set up by the Clinton Foundation to “help support smallholder farmers and families in Africa to meet their own food needs and improve their livelihoods.”

Today, 80 per cent of Anjelina’s field is used to grow a new crop: sunflowers. “The seeds are cheaper than the other products I can plant here,” she says enthusiastically. “And you see how beautiful and tall my plants are. The foundation showed me how to prepare the soil, plant stronger seeds and use fertilizers at the right time.”

Like the six other women members of the Kitowo Village Community Bank we met, Anjelina is not familiar with the SAGCOT Centre and even less so with its role. The women were selected by the Clinton Development Initiative according to criteria such as “having some knowledge of reading, mathematics, and technology, being in possession of a certificate of ownership of the land on which he or she operates,” explains Monsiapile Kajimbwa, the foundation’s agribusiness director at the country level.

The Clinton Development Initiative is one of the stakeholders in SAGCOT, which promotes socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable value chain investments. The organization has developed a program that aims to empower smallholder farmers in Iringa through a community-based agro-industry approach. This allows the community to manage its own seed supply, market it and manage its access to financing.

The women tell us that they have been convinced by the project to plant dry beans. They give credit to the Initiative's staff for training them and donating seeds and fertilizers on preferential terms for the introduction of this new crop.

“I am in the field from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. every day,” one says. "Increasing yields is quite simple, especially with the techniques that we have been shown,” adds another.

Dry beans are a new variety promoted by the foundation. However, one of the main tasks of the initiative’s field officers is to persuade the farmers they will be paid, and that there is a market for new products. Concerns remain, however. One farmer asks: “But where are the customers? Where and to whom are we going to sell these beans?”

Women were given a “list" of potential buyers and seem not to know where the collection centre is located. “They will sell their products. The market is there; there is a market,” confirms Thobias Mville, Manager of Agricultural Development at the Foundation. However, the farmers have not yet met with buyers and no agreement has been made about the quantities that will be purchased from them and at what price.

We learned from the staff of SAGCOT and the representative of the President's Office to the local authority that no system has been created to limit the risks taken by small producers. They themselves bear the risks of this transformation desired by the country. We are told that there is no insurance system for agricultural products and even less aid or protection for small farmers.

Anjelina's assets are her land. What will she do in the event of poor sales or poor harvests? It is very likely that the most vulnerable will be tempted to sell their main source of income.

Day Nine: The power of an entrepreneur

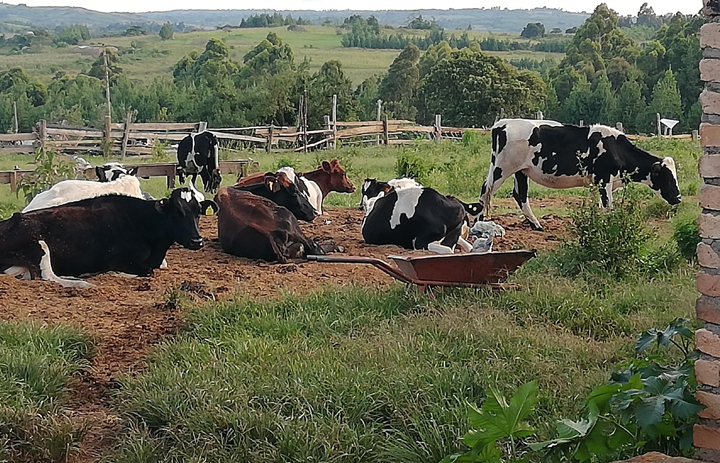

Today we met an inspiring entrepreneur who embodied the concept of agricultural transformation, which involves the economic development from subsistence to commercial agriculture. This dairy farmer, Felix Mpiluka, owns 250 cows and lives in the village of Ilandutwa, in Tanzania’s Southern Highlands. Sixty kilometres away lies the nearest town, Iringa, where he transports fresh milk regularly to the ASAS dairy factory, which we also visited.

His farm has no electricity or running water, and the challenging road conditions between Ilandutwa and Iringa make his work even harder. But none of this deters him: rather than seeing these as barriers, he tells us that these are opportunities to innovate throughout the process.

During our visit, he walked us through each of the innovations that allow him to sustain and grow his dairy business. For example, he uses a brick tub filled with water to keep the milk cool at night before delivering it to the factory in Iringa the next morning. This gives him an extra 12-hour window before the milk spoils.

To clean his metal milk cans, he uses a clay oven, which ensures that the milk he stores and transports meets the highest levels of hygiene and food safety. “This technology was borrowed from what they used to use in Europe,” he said. “We use one log of wood every two days. It is very energy efficient.”

“Our secret to success is to keep it simple. We use simple technologies. Nothing fancy or sophisticated. But we are still able to produce good volumes and high-quality milk,” he told us.

Last year, the local government sent a letter to people in the area saying that opportunities for milk sales were expanding. At the same time, the government announced that they were bringing electricity to the region.

Mr. Mpiluka saw opportunities everywhere and started preparing for the arrival of electricity. He first obtained a loan from the Tanzania Agricultural Development Bank (TADB), which was set up in 2015 to fund farmers and a range of agricultural projects. The loan was used to purchase two cooling tanks that can hold up to 3,000 litres of milk.

“If we keep the milk in these tanks, it stays fresh for three or four days. That means we can now deliver milk to ASAS once or twice a week rather than every day. That is a huge saving in time and transport costs!” he said.

“More importantly, I can now set up a milk collection centre and provide storage and transport service for dairy farmers from the surrounding eight villages,” he continued.

Despite the efforts to bring electricity to the region, there are frequent blackouts. He therefore acquired a generator as a backup system. “I found out that the British embassy [in Tanzania] was selling their old generator, so I went to Dar Es Salaam to find out more. I bought it from them. It is the best brand out there!”

His stories of innovation and entrepreneurship went on and on. “You are a source of inspiration to us and to the people of our countries,” said Nicolas Kobiane from Bagrépôle in Burkina Faso. “Thank you sharing this incredible journey of transformation from subsistence to commercial farming.”

We finished the day exhausted but filled with admiration, humbled by this farmer with his indefatigable spirit, his devotion to his work and his boundless creativity.

Day Eight: Harnessing irrigation's potential in Tanzania

On our first day in Tanzania, a key theme was the importance of developing effective irrigation schemes to support small-scale producers. We were joined by our new IISD Associate, Priscila de Andrade, who contributed to this blog. We met with the National Irrigation Commission of Tanzania (NIC), the central authority responsible for irrigation. We also spoke to officials from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the government aid organization that has focused on improving irrigation systems and productivity in the rice sector since it was established in 1974.

The assessments we heard of Tanzania’s irrigation sector were mixed. “There is insufficient investment, weak participation of the private sector and insufficient investment in the maintenance of irrigation schemes,” said Doris Sendewa, an economist at the National Irrigation Commission.

Despite these challenges, some officials noted that there have been some notable advances, though realizing irrigation’s full potential will require further work.

“We have made good progress and seen important improvements in productivity in the rice sector,” said Mr. Fumihiko Suzuki, Senior Representative of JICA in Tanzania. “But three things are essential for success: first, ensuring good quality materials, second a secure and stable supply of water by managing competition with upstream users, and third, strengthening associations of farmers that use irrigation to ensure proper maintenance and functioning in the long term.”

Government officials from the Green Belt Authority in Malawi also shared their experiences in developing large-scale irrigation schemes. “The best way to avoid failure is to ensure that irrigation development is driven by the demand of the users and not imposed from above,” said Alex Nthonyiwa, an irrigation engineer for the Green Belt Authority. “Equally important is ongoing support and capacity-building activities for the beneficiaries to ensure proper management of the schemes,” added Catherine Wandale, Green Belt Authority’s human resources manager.

We also visited GBRI, a company based in the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor (SAGCOT). GBRI is a domestic private company run by a young female entrepreneur, Hadija Jabiry, that supplies horticultural products such as French beans, baby corn and tomatoes to the domestic market and for export. They have an outgrower scheme that contracts with around 240 smallholder farmers, about 40 of which are women.

“We have been running for three years now and, while we are not yet running a profit, we have a dedicated team and strong partners like SAGGCOT supporting us to success,” said Chacha Magige, Export and Operations Manager.

GBRI is in the Ihemi cluster, which is one of SAGCOT’s flagship clusters. SAGCOT describes this cluster, with its population of 1.64 million people, as having “the potential to produce food crops for almost all seasons,” spanning multiple districts.

Day Seven: Farewell to Burkina

As we prepared to leave Burkina Faso, we took the chance to think back on our time there. The days on the study tour were rich and intense. Government officials from Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Senegal and Togo had a chance to learn from Burkina Faso and share their own vision of using the model of an agricultural growth pole to transform their agricultural sector.

As to the question of whether Bagrépôle is a good model of development or not, we heard mixed views.

“They thought of everything,” said Pyaabalo Alai, a participant from Togo. “Not just physical planning, but social infrastructure—like schools and hospitals. It is all there. Integration of small-scale producers, dams, irrigation, electricity, roads… even a bank. There is an institutional framework, a legal framework and a clear sharing of roles and responsibilities. We in Togo are still a long way away.”

Those in charge of Bagrépôle recognize that they haven’t achieved full success yet but see the project as a work in progress.

“This project needs time. We are only at the start,” said Joseph Martin Kaboré, Director General of Bagrépôle. “This is not just a simple agricultural project. If we want to transform agriculture, there are so many factors to consider that go beyond a narrow sectoral focus or a single infrastructure project.”

On our last day, we also met with a network of West African farmers’ organizations called ROPPA.

“We are in favour of investment,” said the organization’s Executive Secretary, Ousseini Ouedraogo. “But any investment not directed to family farmers is not good.”

He strongly criticized Bagrépôle for not having emerged from a broad national consultation process and for not involving farmers’ organizations in its concept development or design. ROPPA rejects Bagrépôle and instead calls for the implementation of the ECOWAP (the agricultural policy adopted by the Economic Community of West African States), which they support because it reflects a region-wide vision with broad-based support.

Whether you consider Bagrépôle a model to be replicated or avoided, one thing is certain: the men and women who work for Bagrépôle are a highly dedicated team who work hard and want results. They have earned our admiration and treated us to a journey filled with enthusiasm and ambition.

Day Six: Learning from experience

“The project did not work,” said Mr. Roger Kabongo, reflecting on an agricultural project he was involved with in his native Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). “We went too fast and did not respect the procedures. We did not plan effectively. There were no proper feasibility studies or environmental and social impact assessments. No proper consideration of land issues. And we should have integrated civil society from the start.”

Kabongo is in charge of administration and finance at Bukanga Lonzo, an 800-square-kilometre agricultural growth project about 250 kilometres from the capital of Kinshasa. The project was launched in 2014 and was to be administered by Africom Commodities Pty Ltd, a private company based in South Africa. Bukanga Lonzo was the first in what was meant to be a series of parks in DRC, intended to spur increased agricultural production, address local food shortages and attract increased investment in the agricultural sector.

The project has since collapsed. Africom has withdrawn, citing issues with receiving payments from the country’s government. The company has now submitted a multi-million-dollar arbitration claim to recoup those funds.

The concerns Kabongo raised with us echo some of the criticisms made in a recent report by the Oakland Institute, a U.S.-based think tank, which cites problems with a number of aspects of the Bukanga Lonzo project and warns against continuing with the project to build other agricultural growth parks in the country. Others who know the project offer a more tempered assessment, arguing that the significant challenges DRC faces with the project do not invalidate the effort.

For Kabongo, the next steps are clear: “We are not giving up. We want to try again. We want to correct our mistakes. We want to do better.” He told us the government is currently considering establishing four agropoles around the country.

Augustin Mpoyi Mbungu is an Associate at IISD and head of Conseil pour la Défense Environnementale par la Légalité et la Traçabilité (CODELT), a civil society organization headquartered in DRC. He is optimistic: “The experience of Bukanga Lonzo has at least allowed DRC to draw lessons that will support the ongoing process of land reform, starting with the first draft of the national land policy document, which is currently waiting to be validated,” he said.

“A key feature of the draft land policy is social safeguards to limit adverse effects on local rights and interests of the population,” he said. “That will protect local tenure rights holders from the risks of evictions.”

The safeguards currently under discussion in DRC’s draft national land policy document will be binding. They include:

- Collective land titles, based on customary law and with the possibility for individuals to claim title.

- The right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) of the communities and persons likely to be affected by a land investment project.

- The right to compensation for losses or changes to communities and/or individuals, including resettlement.

- The right to participate in decision-making processes.

- The right to resort to more accessible and streamlined justice mechanisms in response to the long delays and heavy procedures in the existing justice system.

DRC’s land reform process is a step in the right direction. We know that the law does not capture every aspect of this challenge and that people need a lot more than laws to protect their rights. Nevertheless, there is some hope that DRC is taking a step toward land systems that recognize all legitimate tenure rights holders, whether formally recorded or not. These systems, when designed and implemented appropriately, provide an essential foundation for responsible investment and sustainable development.

Today’s visits were devoted to education and training projects, giving us a chance to meet students and teachers and learn more about the communities in which they live. We first went to see the Training Institute for Rural Development (IFODER), which teaches improved agricultural techniques, commercialization and marketing to young people, aged 18–25. But many of these students struggle to find work after their training is complete, due to a lack of economic opportunities in the area.

"Few students from the first class have found a job. We need more private investors to arrive to create employment opportunities," said the director, Laurent Kiwallo. He is nevertheless comforted to know that these young people are motivated to contribute to the agricultural sector and have developed vital skills, including getting their driver's licences.

The director envisions setting up agricultural incubators in the region, which are mechanisms meant to make it easier for small agriculture-focused companies to grow and innovate, such as by providing them with financial services. These incubators would, in turn, help stimulate innovation and create jobs.

We later visited a primary school for 220 students set up by Bagrépôle, which has agreements in place with Burkina Faso’s Ministry of Education for getting teaching staff assigned to the school. "We currently have three grades at the school, for six- to eight-year-olds. It's a good start, but we hope to obtain from the ministry the possibility of having a complete primary school with all the grades," said a young teacher we met, speaking in front of his students.

The challenges of providing basic education, creating jobs and developing lasting economic opportunities in this area are significant. While Bagrépôle has already set up several training, capacity-building and support projects, improving markets to ensure these students have job opportunities as adults will be one of the next hurdles to face.

Day Four: At Bagrépôle, steps forward but still more to do

Today we visited Bagrépôle, a pilot agricultural investment project launched in 2012. There we met farmers, the project team, company representatives and the many other actors who count this project as part of their daily lives.

Bagrépôle representatives told us that, while there have been some notable advances over the past seven years, there have also been some tough setbacks along the way and the project has moved more slowly than planned. They said more work remains to realize their vision.

For example, they told us how they are still trying to build the supporting infrastructure and that only a handful of domestic companies have invested—far fewer than the 108 domestic and international companies that Bagrépôle identified at an international conference years ago.

The feasibility studies done when the project began were not of sufficiently high quality. They could have done more to identify the complex land issues, environmental challenges and technical problems that have come up during implementation. Officials also told us the land cost more to develop than originally anticipated, making it harder to move as quickly as they had hoped.

Their message to other countries interested in building agricultural investment hubs is that they require time, resources, political buy-in and a clear long-term vision. Any investment project of this magnitude, they stressed, requires a strong foundation, one that actively engages small-scale producers and affected communities.

We spent much of the day meeting some of those local farmers and visiting projects set up under Bagrépôle to support them.

Halidou Dabré is a rice farmer we met. He has 1 hectare of land, is supported by an extension worker and gets subsidized inputs from Burkina Faso’s Ministry of Agriculture. He says he is grateful for the support given by Bagrépôle, but told us he hopes to see more.

"Bagrépôle has provided us with irrigation so we can now plant two or three times a year, which has greatly improved our revenue," he said. But he also noted the high costs of inputs and fees for using water infrastructure.

Dabré is part of a cooperative and therefore benefits from the collective negotiations and sales to a nearby miller. Over 100 farms like his exist, though the representatives from Bagrépôle told us that it is not yet enough. Many other farmers have been promised land but are still waiting for their parcels.

We also met Xavier Zidouemba, a banana farmer with a 4-hectare plot. He’s also part of a cooperative with 19 other farms. Bagrépôle has facilitated the cooperative’s access to technical support through a project funded by the German government, which made it easier for them to get credit from a local bank. “They help facilitate access to extension workers, inputs and credits, which helps," he said.

He too hopes more support will come. For instance, he told us he’s struggling with the “insufficient availability of training programs and an absence of improved varieties of banana.”

We then met a few domestic companies providing seeds, inputs, credit and access to regional markets in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, trying to open up opportunities for trade. We learned about a range of activities trying to provide access to credit for farmers and set up value-added industries, with a strong focus on women, including five centres for making cloth and a tomato pulp factory.

We saw an impressive irrigation system connected to a pre-existing dam, which provides water to small farms through a series of canals. Bagrépôle includes small-, medium- and large-scale farms ranging in size from less than 5 hectares to over 50.

The officials on the tour from other countries are listening attentively. Bagrépôle is not the success story they hoped to find. But we met an incredibly dedicated and committed group of people who enjoy strong political support and buy-in across multiple ministries, and who are working in a coordinated way to make this investment work for the people of Burkina Faso.

There are no magic solutions, but the rich experiences shared today offer much for others to learn from as they think of what their own countries need.

Our first two days were spent in Burkina Faso’s capital, meeting with government officials from this country and hearing their feedback on land tenure issues and land rights. Today we headed out to visit the agropole in Bagré, in the southeastern part of the country.

But first we checked in with some of the people on the tour to find out what they have learned so far and what they wish to learn more about in the days to come.

Lié Maminiaina from Madagascar told us that one of her greatest takeaways so far is the value of setting specific priorities when establishing an agropole, which could then help guide the project from start to finish. Above all, she said, the development of any agropole project must be driven by the core objectives of “eliminating poverty and ensuring food security.”

These projects also must be inclusive from the outset, ensuring that civil society, small-scale producers and the domestic private sector are involved from conception to implementation. Bagrépôle, for example, has among its partners the local Chamber of Commerce and the Maison de l’Enterprise. Also critical is exploring contract farming models when setting up these growth projects, she said.

Lié remarked on how important it is to make sure the populations affected by these projects are kept informed and engaged throughout, making sure they have a chance to provide feedback. She flagged the establishment of Radio Bagré, with broadcasts planned in multiple languages, as an example worth exploring.

For agropoles to be successful, they also need supporting infrastructure and related public investments, along with political will. Yet there are a few other key components to agropoles’ success, making sure these projects go beyond the singular goal of transforming agricultural production. These considerations will help ensure that agropoles support the achievement of sustainable development objectives and do not create new problems—or exacerbate existing ones.

“Land issues must be managed carefully so that no one is harmed,” Lié said. That point came up repeatedly during our discussions on Tuesday with government officials. Also essential is making sure “high-quality” feasibility studies, as well as environmental and social impact assessments, are conducted before any decision is taken to launch an agricultural investment project.

Project oversight is also key, and that will require the right institutional framework in place, as well as the involvement of the relevant ministry, she said.

Discussing these core issues with Lié—inclusiveness, environmental and social considerations, and the different supporting roles that key actors can play—left us feeling inspired. We look forward to updating you all tomorrow with what we’ve seen from the field.

Day Two: At issue, land rights

On our second day, the challenge of land rights and land tenure systems came up often. For almost all of the government officials on this tour, land is the primary and most pressing challenge. Identifying and protecting the rights of local landowners and users within existing land tenure systems continues to be a source of difficulty and tension. All agree that these land rights, whether formal or informal, must be clearly identified and respected.

But how to do that?

First, most of the countries on this tour have either recently completed or are in the process of reforming their land laws to strengthen tenure rights for those with insecure or informal rights: Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali and Senegal. That’s a good sign.

Second, international standards now exist that provide guidance on responsible land governance, including the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security and the Framework and Guidelines on Land Policy in Africa.

And third, when land is acquired for investment, affected people must have a say. The principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent represents an important tool for local communities. It requires proper information and consultation for the communities as well as the possibility to reject a project.

The principle is enshrined in international law only for Indigenous peoples at the moment, but its application is also expanding to local communities more broadly and is reflected in some of the International Finance Corporation’s operational frameworks.

Tomorrow we head out to visit the agropole in Bagré.

Day One: Our journey begins...

Today we began a two-week study tour of agricultural growth poles (agropoles) and corridors, a trip that will take us to Burkina Faso and Tanzania.

We will use this blog to share stories of the people we meet and those who are joining us on the tour, with the aim of exploring the pros and cons of this growing trend.

The idea was born a year ago: government officials across Africa, spearheaded by Madagascar, asked for an in-depth look into how agricultural investment projects were performing in practice. Many of these governments are struggling to attract private investment into rural areas, and are curious to learn more about economic zones, agropoles, parks and corridors, which are already being seen in Asia.

These projects are being tested as possible tools for adding value to primary agricultural production and developing agro-industries, with the ultimate goal of strengthening food security and reducing poverty. However, the experience in Africa has largely been negative. Projects have been drawing heavy criticism for excluding small-scale producers, undermining food security and land grabbing. These problems have been well documented by the IMF, FAO, and the World Bank, among others. Some have even called for the projects to be stopped altogether, including ROPPA, Oxfam and the Oakland Institute.

So why are we taking this trip and what do we hope to achieve?

For over a decade, IISD has been advising governments and parliamentarians on how to attract responsible agricultural investment to achieve sustainable development. Increased private investment, when conducted responsibly, can boost agricultural production, generate employment, raise incomes and promote economic development. But when done badly, this investment can exacerbate poverty and inequalities, violate tenure rights, undermine small-scale producers’ livelihoods, with particularly damaging implications for women, and significantly deplete natural resources. The government officials with us during this tour are aware of these risks and want to mitigate or avoid them.

Given the grave risks, IISD does not promote or advocate in favour of agropoles, corridors, or any other specific tools for attracting responsible agricultural investment. But we do believe that private investment is needed to achieve sustainable development, so we work with governments to develop robust legal and policy frameworks that maximize the benefits of this investment, while minimizing its risks.

We hope the government officials joining us on this tour will be able to get answers to some of their questions and concerns about agropoles and corridors. We also hope to develop greater insights into what works, what doesn’t, and how things can be done better.

- Francine Picard and Carin Smaller

Bookmark this blogpost and check back for updates.

You might also be interested in

CSDDD: EU's Due diligence law vote should drive supply chain sustainability efforts

The European Parliament has voted to adopt the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, aiming to address the environmental and social impacts of the supply chains of Europe's large corporations.

IISD Mourns the Passing of Ciata Bishop, Advisor and Advocate for Responsible Agricultural Investment

IISD is saddened by the recent loss of Ciata Bishop, a longtime friend and advisor to our team, and a passionate advocate for ensuring that investment is conducted sustainably and with the involvement of the communities affected.

Mahembe Coffee

This case study analyzes the extent to which a small agribusiness in Rwanda complies with international standards for responsible investment in agriculture.

Sénégalaise des Filières Alimentaires

This case study analyzes the extent to which a small rice miller in Senegal complies with international standards for responsible investment in agriculture.