Belief in Climate Change in the Age of Trump

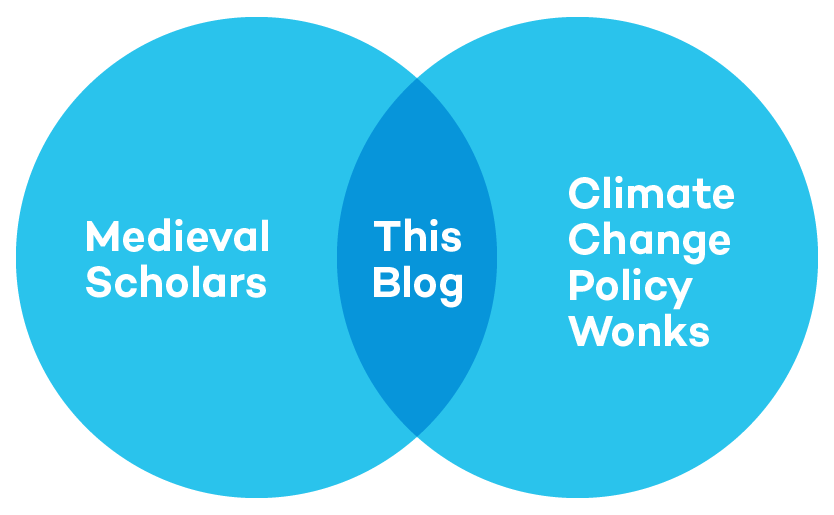

Will more evidence affect climate action, or are we entering a new Dark Age characterized by willful ignorance? Scott Vaughan reflects as COP24 struggles to make the necessary progress.

I’ve been thinking about Donald Trump, Thomas Aquinas and The Monkees a lot lately — especially with the lack of progress coming out of the UN Climate Change Conference in Katowice, Poland (COP24).

Let me start with Aquinas. Six hundred years ago, his work explored the relationship between faith and reason and showed they were not contradictory, but indeed complementary. This turned the page on the centuries that preceded him, a time we now know as the Dark Ages.

Aquinas’ work helped set the stage for subsequent schools of philosophy—including Kant, Hegel and the British empiricists—that probed questions such as “How do we know what we know?” and “What underlies the relationship between belief and evidence?”

Aquinas noted belief (specifically the medieval world of religious belief) came first, but was not contradictory to the world of evidence:

We can't have full knowledge all at once. We must start by believing; then afterwards we may be led on to master the evidence for ourselves.

Fast forward to Donald Trump.

Asked about the findings of his own federal interagency task force, which examined the effects of climate change on the United States, he replied: “I don’t believe it.”

Rather than disagreeing with the contents of the report—for example, disputing key findings—his lack of “belief” silences hundreds of experts who worked to summarize the state of empirical knowledge about climate change and America.

This U.S. report—released the day after Thanksgiving, no doubt in an effort to bury the headline—is the latest in a sobering string of reports tracking climate trends and projected impacts:

- UN Environment reported that greenhouse gas emissions rose in 2017, following a three-year downturn, and warned there are signs of global emissions peaking.

- The World Meteorological Organization reported that the world is on track to an average temperature increase of between 3 and 5 degrees Celsius. The lower estimate of 3 degrees is the current best-case scenario if all countries meet their climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change described the consequences of missing the Paris climate target (an average 1.5 degree Celsius temperature rise). These include premature deaths, crop failures, flooding and sea-level rise, and more.

These three topics—observed greenhouse gas emissions and projections, observed changes in global average temperatures and the consequences of temperature increases—represent the evidentiary foundations of climate change.

The recent report of the United States federal inter-agency work on climate change—the Fourth National Climate Assessment—similarly examined these areas and looked at consequences at the national level.

The U.S report is significant for three reasons. First, it focuses climate analysis at the country level, examining issues like public health, infrastructure, national security and economic livelihoods. Second, it includes agencies beyond the Environmental Protection Agency, NASA or the Interior, also bringing in the Pentagon, Commerce, Energy, Transportation and State departments. And third, Trump’s own White House signed off on the findings.

The report notes, factually, global average temperatures have already increased by one degree Celsius in the past century. The last few years have seen “record-breaking, climate-related weather extremes, and the last three years have been the warmest years on record for the globe.” Heatwaves are expected to become more common. Large forest fires in the Western United States and Alaska are expected to increase.

With these warming trends, sea levels globally have already risen by seven to eight inches in the past century. They’re expected to continue rising by at least several inches in the next 15 years, by one to four feet by the end of the century, and potentially by eight feet by the year 2100.

The report also unpacks deepening risks from these trends; notably, climate change is expected to cause substantial losses to infrastructure and property and impede the rate of economic growth over this century, unless there are significant measures to mitigate climate trends. This core finding showing the economic costs of climate change builds on earlier work, including that of Nobel Prize-winning economist William Nordhaus, who warned climate impacts can be compared to more familiar economic shocks, including recessions and depressions.

So, in the face of all these detailed analyses, and all the economic predictions, Trump’s “I don’t believe it” raises a basic question: Will more evidence have people saying "I'm a believer," or are we moving closer to a new Dark Age characterized both by accelerating climate impacts and wilful ignorance called beliefs?

As Katowice flounders, the latter seems to be the case.

You might also be interested in

Nordhaus Nobel Recognizes What We've Long Known: Carbon pricing works

In 1984, Nordhaus concluded climate change is real, its impacts are global and comparable to economic depression, and it's likely to occur in sudden jolts.

COP 29 Outcome Moves Needle on Finance

In the last hours of negotiations, concerted pressure from the most vulnerable developing countries resulted in an improved outcome on the finance target, with a decision to set a goal of at least USD 300 billion per year by 2035 for developing countries to advance their climate action.

The Triple-COP Year: What it means for nature

In 2024, the Rio Conventions on biodiversity, climate change, and desertification will have their negotiations in the same year. We take a look at the implications for nature.

IISD Annual Report 2023–2024

While IISD's reputation as a convenor, a trusted thought leader, and a go-to source on key issues within the sustainable development field is stronger than ever, the work happening outside the spotlight is just as valuable.