Global Dialogue on Border Carbon Adjustments

Stakeholders' perspectives in Brazil, Canada, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam

This report contributes to the global BCA discussion by summarizing country-level reports reflecting dialogues conducted in Brazil, Canada, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam. (Download PDF)

1.0 Introduction

As countries increase their climate change mitigation ambitions, they are considering establishing border carbon adjustments (BCAs), a mechanism through which the carbon emissions embedded in certain imports are taxed at the border. Efforts to price carbon domestically can result in displacing economic activity and, therefore, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to other jurisdictions with less ambitious climate policies—this is called carbon leakage. Implementing BCAs could complement domestic climate change mitigation measures to avoid leakage.

The European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom are first out of the gate. Under the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism's (CBAM's) transition period, since 2023, importing companies must report import-embedded emissions; starting in 2026, fees based on said emissions will apply. The United Kingdom will implement its CBAM starting in 2027 without a transitional phase.

In the United States, four proposed bills would impose carbon-related charges on imports: Three would impose a domestic carbon price and levy fees on imports. A fourth would impose border charges but no domestic carbon price. More generally, carbon leakage is becoming increasingly politically salient in the United States, as illustrated by the launch of the White House Climate and Trade Task Force.

Australia and Canada have consulted on a BCA. Such a system has also been mooted in Japan. Chinese Taipei's 2023 Climate Change Response Act includes a BCA, although its 2024 implementing regulation does not yet (Ministry of Environment, 2024; Yu-Shiuan, 2024).

This report contributes to the global BCA discussion by summarizing country-level reports reflecting dialogues conducted in Brazil, Canada (Commission on Carbon Competitiveness, forthcoming), Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam. These dialogues gathered stakeholders' views from government, industry, finance, labour, academia, and civil society. The dialogues were conducted in 2023 and 2024 by IISD partner organizations: the Centre for Studies in Integration and Development (Brazil), the Commission of Carbon Competitiveness (Canada), the University of West Indies (Trinidad and Tobago), Chatham House (United Kingdom), and the Foreign Trade University (Vietnam).

Given their governments' policy objectives and the characteristics of their international trade, these countries illustrate different aspects of BCA opportunities and challenges. As discussed above, Canada is considering a BCA, while the United Kingdom is already designing specific elements of its system.

As shown in Figure 1, these five countries also exhibit varying levels of exposure to the EU CBAM and other jurisdictions adopting BCAs: Trinidad and Tobago and the United Kingdom appear to be the most exposed to the EU CBAM by share of exports in the covered goods.

Over the last 10 years, the share of CBAM goods exports to the EU has tended to increase for some of the countries covered there. The most recent increase for the United Kingdom was probably temporary: in 2022, lower power generation due to nuclear power plant maintenance in France induced higher British electricity exports. For Trinidad and Tobago, the trend can be linked to a sharp increase in overall EU imports of fertilizers since 2020. For Vietnam, higher iron and steel exports to the EU, which increased threefold between 2019 and 2022, drive this shift, possibly due partly to the 2020 European Union-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement. More broadly, though, the countries covered (except the United Kingdom) export their emissions-intensive products mostly to various markets outside the EU, indicating that regulatory divergence caused by the multiplication of BCAs might create additional challenges for their exports.

IISD-supported research shows that Canada faces a high risk of leakage by 2030 under announced climate policies in four sectors.

2.0 To BCA or Not to BCA? The quest to prevent carbon leakage

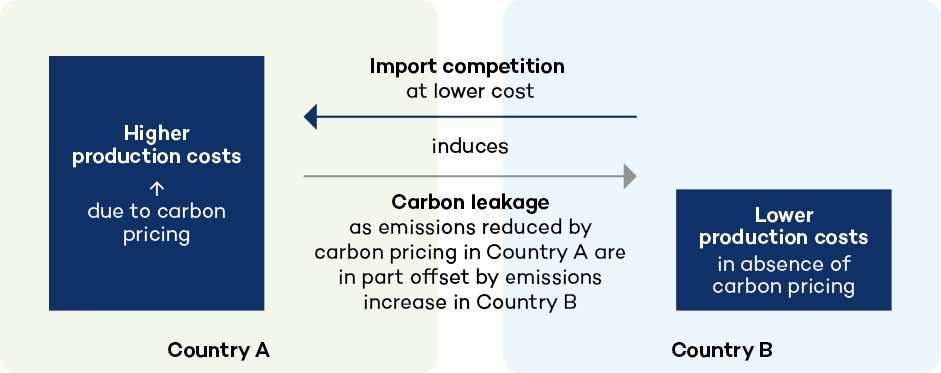

International differences in carbon pricing pose a carbon leakage risk: higher carbon prices in a given country induce imports from countries with less stringent environmental policies. Thus, the emissions of the former countries are partially displaced to the latter: they "leak."

Using the example of Canada, we show how BCAs are one of several policy options for addressing this risk.

IISD-supported research shows that Canada faces a high risk of leakage by 2030 under announced climate policies in four sectors (iron and steel, basic chemicals, fertilizers, and pulp and paper) and a medium risk for cement (Commission on Carbon Competitiveness, forthcoming). Announced policies include an industrial carbon price of CAD 170/tonne by 2030. These policies are forecast to substantially impact costs incurred by industries. For the cement industry, announced climate policies, including the Canadian carbon price, will result in a carbon cost by 2030 that is 1.9% of sales value and 14.4% of operating profit margins. This is a substantial increase over 2023 (Figure 3). Note: The costs incurred are only part of the determinants of leakage risks. Trade exposure plays a significant role. Therefore, the most carbon leakage-exposed industries are not necessarily those incurring the highest costs.

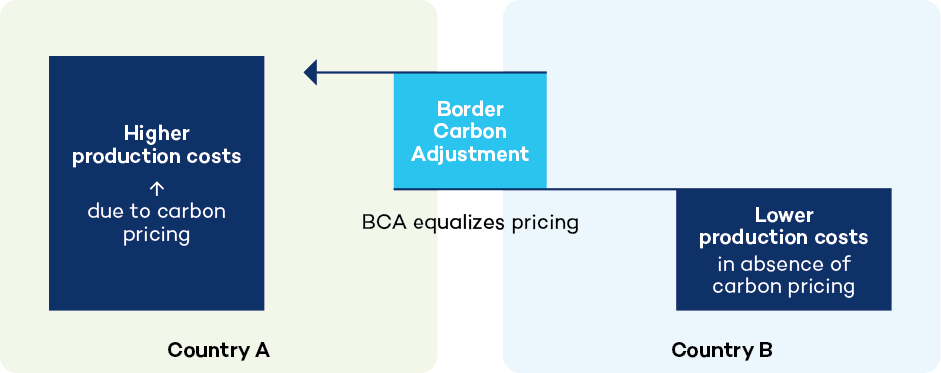

BCAs can address this risk by equalizing carbon prices paid by domestic and foreign producers in the importing market: a fee is imposed on imported carbon emissions. A meta-analysis shows that "detailed numerical analyses using multisector, multi-region models consistently find significant potential for BCA to reduce leakage rates."

BCAs are not simple for the countries adopting them. They may increase consumer prices, be administratively complex, and should be carefully crafted to ensure World Trade Organization (WTO) compliance. Section 3 further explores potential drawbacks and discusses possible remedies. Given those challenges, the Canadian case study assessed the following alternatives to BCAs.

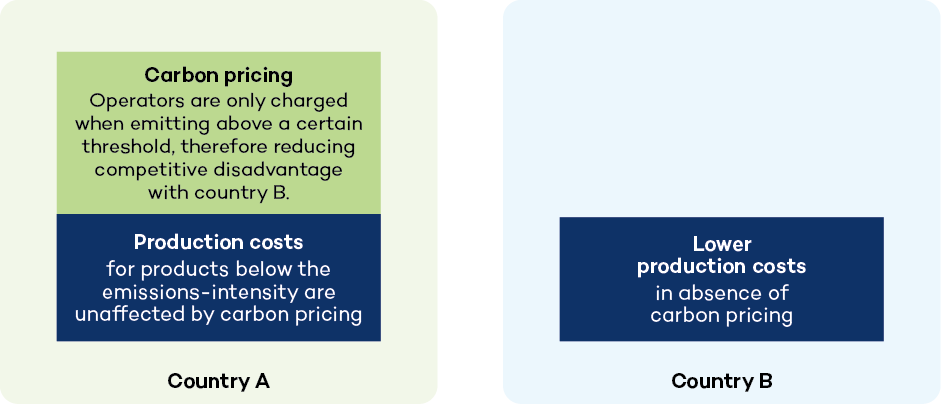

Output-based allocation is like free allocation in the EU's emissions trading system (ETS): Canada's output-based pricing system sets sectoral emissions intensity standards, and GHG-intensive firms must pay when emitting over the standard. They can also purchase credits from firms that emit below the standard. This policy keeps the average costs of carbon low, meaning less impact on prices and less leakage risk. However, it can also blunt the incentives to decarbonize, so the EU is abandoning free allocation and relying instead on the CBAM.

Green industrial policy support: Support for decarbonizing production processes can lower compliance costs with climate policies and thus lower the risk of leakage. However, this approach might be fiscally costly. It also requires strong capacity from policy-makers and institutions to target only specific market failures. In the Brazil dialogue, stakeholders feared that the possible increase in EU subsidies, as the EU is removing free allocation, could be detrimental to the bloc's trading partners.

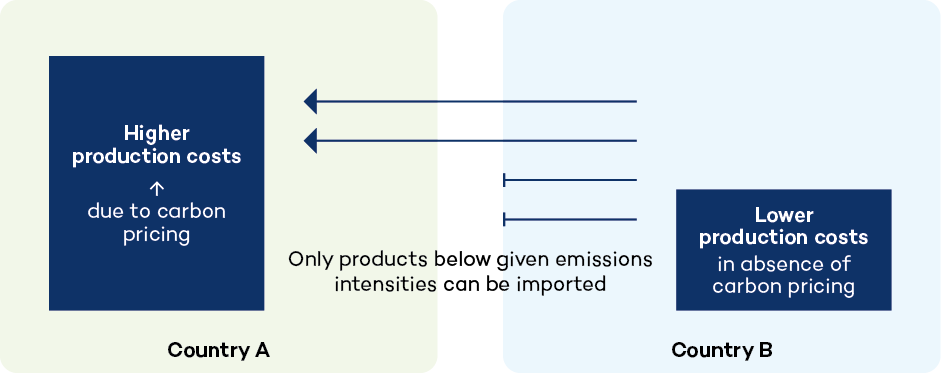

Product-based GHG intensity standards: These standards would be a condition for sale on the domestic market and apply to domestic and imported goods, reducing leakage risk. Yet, if implemented in isolation by a mid-sized economy like Canada, this approach might create disincentives for trading partners to export there rather than improve their emissions intensities. The United Kingdom dialogue also expressed doubts about this policy's viability.

In summary, BCAs are not the only response to carbon leakage. While the stakeholder dialogues summarized below focus on BCAs as a policy option, other options exist.

3.0 How to BCA? Stakeholders' perspectives on principles and best practices in BCA design

3.1 What Goods/Sectors Should BCAs Cover?

Both the United Kingdom and EU CBAMs focus on upstream products. The EU CBAM covers aluminum, electricity, cement, fertilizers, iron and steel, and hydrogen. It also includes a few downstream products, such as iron screws and bolts. The UK CBAM is similar, except it also covers glass and ceramics but excludes electricity.

Both mechanisms may expand to other goods and sectors in the future. By the end of the CBAM's transitional phase (the end of 2025), the EU Commission will evaluate the need to expand it to additional goods and sectors covered by the EU ETS. In the United Kingdom, the public consultation concluded that UK CBAM should allow for coverage expansion in the future.

Some stakeholders fear that expanding the EU CBAM to other sectors covered by the ETS could impact some of their exports, particularly liquefied natural gas and methanol in Trinidad and Tobago, as well as plastics, glass, and ceramics in Vietnam. Stakeholders in Trinidad and Tobago recommend transparent criteria for adding new products subject to BCAs based on pre-defined factors such as emissions intensity and leakage risk.

3.2 Which Scopes of Emissions Should the BCA Cover?

BCAs can cover direct emissions from the production process (Scope 1); emissions from purchased electricity, steam, heat, and cooling (Scope 2); or various types of Scope 3 emissions (e.g., from purchased input goods or from transport). The EU CBAM currently covers Scope 1 emissions for all CBAM products. It also requires reporting Scope 2 emissions, specifically for fertilizers and cement. It covers specific Scope 3 emissions: emissions from precursors that are themselves CBAM-covered goods. The UK CBAM plans to cover some Scope 3 emissions on select precursors, like the EU CBAM, but all Scopes 1 and 2 emissions.

Some stakeholders oppose broader scope coverage. In particular, according to stakeholders in Trinidad and Tobago, reporting on Scope 3 emissions would be challenging and would require significant efforts from their government to build capacity among firms.

In other instances, scope expansion is seen favourably, as it may favour national competitiveness: Brazil has some of the cleanest electricity production in the world. If only direct emissions are considered, then the energy-intensive sectors may lose one of their main comparative advantages.

3.3 How Should Embedded Emissions Be Measured and Reported?

BCAs require emissions accounting at the product level. Accounting protocols under national carbon pricing typically measure emissions at the facility level, not the product level. Instead, BCAs inherently focus on the imported products themselves. This can be challenging. The CBAM has had to develop sui generis product-level methodologies. Product-level accounting is also inherently complex for installations that produce many covered products under one roof.

Stakeholders insisted that the EU CBAM should recognize multiple carbon reporting standards. The Brazilian National Confederation of Industry argued that the EU should also accept international reporting standards, such as the GHG Protocol and International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards, as well as national measurement, reporting, and verification approaches. Stakeholders in Trinidad and Tobago recommended international cooperation to develop new, broadly recognized methodologies to measure and verify product-level emissions.

Brazilian stakeholders also criticized the EU CBAM for the stringency of the carbon measurement process. One of the three monitoring methodologies for direct emissions under CBAM is a measurement approach involving continuous monitoring that does not allow for in-house laboratory measurements. Stakeholders argued that this approach is extremely restrictive compared to the methodologies practiced by the Brazilian industry.

Default values can represent a practical alternative to costly and complex emissions measurement. In the EU CBAM's transition period, reporting can rely on default values estimated for each product and trading partner. Yet, from 2025, default values can only be used for input goods (precursors) and cannot represent more than 20% of embedded emissions. The EU CBAM default values are set relatively high to encourage the use of actual data. In the case of electricity, all emissions are estimated based on default values reflecting average intensity. Instead, the British government plans to give importers the freedom to choose between actual data and default values. This is in line with requests by most stakeholders at the government's consultation. The dialogue in Trinidad and Tobago highlighted that default values are an essential alternative to actual data, but some stakeholders worried that said default values might be set at a punitively high level.

3.4 How Should BCA Revenues Be Used, and How Can Those Negatively Affected Be Supported?

Several stakeholders in Brazil, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam have advocated for BCA revenue to be allocated to decarbonization and mitigating the adverse side effects of BCAs. This contrasts with the current plans of the EU and the United Kingdom, which intend to allocate this revenue to their general budgets.

Yet, the question of repurposing funds for decarbonization also poses equity concerns. Stakeholders in Brazil feared that using revenues to decarbonize domestic industries in countries applying BCAs would increase the competitiveness gap vis-à-vis exporting companies from other jurisdictions.

3.5 How Should Foreign Action Be Credited?

Should the BCA charge be lowered to account for a carbon price paid in the country of export? With the EU CBAM and the UK CBAM, explicit carbon prices paid for in the origin country are deducted from the CBAM fees (i.e., any tax or ETS fee targeting carbon explicitly—but not excise fuel taxes).

Stakeholders in Trinidad and Tobago advocated for a broader recognition of decarbonization efforts, including those linked to non-price-based climate policies. Such policies included regulations that impose a cost on producers.

Brazilian stakeholders have also called for carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) to be accounted for when measuring and reporting emissions. CCUS consists of the on-site capture of emissions. Brazilian stakeholders argued that CCUS was necessary for hard-to-abate sectors. Under the EU CBAM, CCUS can be considered when calculating embedded emissions in CBAM goods, as long as specific criteria are satisfied. These criteria primarily require that the captured carbon dioxide is either used to manufacture products where it is permanently chemically bound or transferred to a long-term geological storage facility. Brazil’s National Confederation of Industry, in its submission to the European Commission's 2023 call for feedback on the EU CBAM implementing regulation, contended that provisions regulating CCUS may hinder the accounting of this technology. Note: One should note that, while this critic was aimed at the draft and not the official implementing regulation, the two versions are similar when it comes to CCUS provisions, as laid out in point B.8.2. of Annex 3.

Finally, the dialogues in Vietnam have revealed the importance of carbon offset mechanisms to the country’s decarbonization policies. Offsets consist of compensating emissions with reductions in emissions achieved by some entity outside the facility. Currently, the EU CBAM and the UK CBAM do not recognize offsets, as their respective ETSs do not recognize them either. While specific offsets could be used for EU ETS compliance until 2020, this is no longer the case due to concerns regarding their reliability.

3.6 Should Some Countries Be Exempted Based on Their Development Level?

There are no plans to exempt any countries, depending on their development level or other circumstances, from the EU CBAM or the UK CBAM.

Stakeholders across various countries' dialogues suggested exempting developing countries, specifically least developed countries. The dialogues in Vietnam highlighted that the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities, enshrined in Paris Agreement Article 2, stipulates that development status should be reflected in each country's mitigation obligations. In Trinidad and Tobago, stakeholders argued that Small Island Developing States should receive specific exemptions.

The dialogues in Vietnam stressed that historical emissions should be considered when determining a given country's obligations under BCAs. They highlighted that the EU and the United Kingdom accounted for 22% of global historical emissions since 1751, whereas China was only responsible for 12.7% of the total.

Beyond these general design features, more specific aspects emerged in the dialogues in Canada and the United Kingdom: They relate to BCA phase-in (Box 1) and the possibility of imposing BCA fees from a given emissions intensity threshold (Box 2).

According to some stakeholders in Vietnam, awareness raising remains a challenge and should be amplified.

4.0 How to React and Adapt to BCAs: Stakeholders' perspectives on policy responses from countries affected by their trading partners' BCAs

4.1 Raising Awareness

Participants in Trinidad and Tobago and Vietnam presented awareness raising as a cornerstone of preparing their trading partners' BCAs. Business associations played a crucial role in these efforts. Sometimes, they cooperated with international partners, such as the EU and the Caribbean Export Agency. According to some stakeholders in Vietnam, awareness raising remains a challenge and should be amplified.

4.2 Developing/Accelerating Domestic Carbon Pricing

Some stakeholders in Brazil, Trinidad and Tobago, and Vietnam consider developing or accelerating domestic carbon pricing as an effective policy response to BCAs. It has the advantage of lowering BCA fees incurred by exporters and retaining the revenue in the country of export. It also prepares firms by requiring them to measure and report their emissions. Vietnam plans to initiate an ambitious pilot carbon credit exchange in 2025.

4.3 Challenging BCAs Legally

There are concerns about BCAs' compatibility with international trade law.

According to the European Commission, the EU CBAM has been designed to be compatible with WTO rules. Similarly, the dialogue in the United Kingdom pointed out that legal analysis undertaken by the industry, particularly steel, concludes with the compatibility of EU CBAM and WTO rules. However, stakeholders in Trinidad and Tobago believe it may violate the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade principles of non-discrimination by treating nations differently, particularly between EU member states, European Free Trade Association countries, and others. Moreover, in Vietnam, stakeholders suggested that the EU CBAM may also violate the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement. Yet, stakeholders in Vietnam also pointed out that resolving those issues through dispute settlement might be lengthy and ineffective.

A radical response to BCAs can also be fully integrating pricing systems across countries. As this option is inherently politically challenging—it has only been achieved once between two particularly close trading partners—it is presented separately in Box 3.

5.0 The Way Forward

Dialogues with stakeholders across Brazil, Canada, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam illustrate how BCAs can represent a response to carbon leakage risk. Yet many questions remain regarding their acceptability and fairness.

While BCAs are intrinsically unilateral measures, stakeholders have called for their implementation to be accompanied by multilateral discussions at international forums such as the WTO or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Dialogues in Trinidad and Tobago and Vietnam highlighted the need for global coordination on reporting standards. Brazilian stakeholders advocated for partnerships with other developing countries to face BCA related challenges.

In this context, technology transfers are sometimes seen as a central aspect of international cooperation. Stakeholders in Trinidad and Tobago described technology transfers as the most critical aspect of the BCA debate. Vietnamese participants stressed its role in decarbonizing power generation and improving the energy efficiency of industrial processes.

The dialogues across all five countries reflect that BCAs are increasingly seen as an inevitable trend one needs to get right rather than oppose. Developing common principles to guide the design and implementation of BCAs will ensure they achieve their objective of mitigating carbon leakage without causing unnecessary trade frictions.

A full list of references can be found here.

Participating experts

You might also be interested in

Border Carbon Adjustments: Pivotal design choices for policy-makers

This policy brief covers the pivotal choices in the design of border carbon adjustments, aiming to provide useful insights to policy-makers and set the ground for the broader discussions about the best practices.

Border Carbon Adjustments: Priorities for international cooperation

This IISD policy brief looks into border carbon adjustment design elements that are priorities for international cooperation, as well as the possible venues, formats, and shapes that such a discussion might take.

Net-Zero Should Not Be a Net Loss for Low-Income Economies

As countries make the transition towards net-zero economies, what do these policies mean for international trade?

Can Trade in Electric Vehicle Raw Materials Create Development Opportunities?

As demand grows for electric vehicles, there are valuable lessons to learn from Chile and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.